by Irineu Franco Perpetuo

Collection conceived by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and launched in the world by Naxos reveals treasures of Brazilian concert music

The country that prides itself most on its popular music has finally decided to discover for itself – and reveal to the world – its concert production. With the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra, the Minas Gerais Philharmonic and the Goiás Philharmonic, the series A Música do Brasil (‘Music of Brazil’) reaches its thirteenth album release this month, distributed internationally by the Naxos label.

The series began in 2019 with an album dedicated to Alberto Nepomuceno (1864–1920) with the Minas Gerais Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Fabio Mechetti, which immediately caught the attention of international critics: BBC Music Magazine described the album as “inspiring”.

Since then, the Brazilian canon has been widely explored, always with a warm welcome: volume 7, in which Emmanuele Baldini (violin) and Pablo Rossi (piano) play Villa-Lobos’ sonatas, has just been nominated for the Latin Grammy. And the most recent album, in which the Minas Gerais Philharmonic plays works by D. Pedro I, won praise from Gramophone magazine – not only for the music (Te Deum is hailed as a work of “tremendous exuberance”), but also for the performance (“the reliable orchestral direction of Fabio Mechetti”) and the technical quality (“the recorded sound, captured in the Sala Minas Gerais, in Belo Horizonte, is exemplary”).

The project

‘Music of Brazil’ belongs to a larger project of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brazil in Concert, which aims to promote and disseminate internationally the music of our composers. The initiative came from diplomat and composer Gustavo de Sá, head of the cultural sector of the Brazilian embassy in Lisbon. At the end of 2016, he was head of the Brazilian Culture Promotion Actions Division. And he was delighted with an album in which the Goiás Philharmonic, conducted by Neil Thomson, performed three orchestral pieces of Guerra-Peixe (1914–93): The removal of the lagoon, Concertino for violin and small orchestra (with solo by Abner Landim) and Museum of Inconfidência. “I could hardly believe the quality of the record: it was an orchestra from the interior of the country, of which no one had heard, and even in the classical world it was not very well known,” recalls Sá.

The pianist Sonia Rubinsky, who had recorded the complete piano works of Villa-Lobos for Naxos (and then participated in the series with a recording of piano pieces and orchestra by Almeida Prado, with the Minas Gerais Philharmonic), made the bridge with the label.

And Naxos was the right partner. “When I was young, Brazil was the land of my dreams and I was planning to emigrate and live there,” says Klaus Heymann, founder and president of Naxos Music Group. The idea of living in Brazil did not become reality, but interest in the country remained. “Brazilian music has to be heard more in the world. Music editors who control the works of the major composers have to make a greater effort to get the music performed. And we need more Brazilian musicians at an international level that can help promote the country’s music,” says Heymann, who embraced the project from the very first moment.

From his previous attempts to get Brazilian works programmed outside the country, Gustavo de Sá knew that the absence of records and scores were the main obstacles: “There were a few bad recordings, and the scores were in manuscript, or in xerox, or were bad editions,” he says.

From this came the idea that Itamaraty would act as coordinator of the initiative, organising the relationship between orchestras, Naxos and the editions of the scores by the Brazilian Academy of Music and Musica Brasilis. “An institution alone can’t do much,” says Sá. “It is up to the ministry to articulate the Brazilian cultural environment and the external industry for dissemination abroad.”

Sá explains that the ministry did not hire the orchestras, but proposed a partnership, arousing the costs of recording. “Orchestras absorb this repertoire in their seasons. Thus, to produce external action, we end up creating internal impact. We put this music in the repertoire of Brazilian orchestras, to run within the country. Many of them are debuting.”

Repertoire

Even in the consolidated repertoire, there was work to be done. Gustavo de Sá cites the album with openings and orchestral excerpts of the operas of Carlos Gomes (1836–96) conducted by Fabio Mechetti that the Minas Gerais Philharmonic launches in March next year. “When we put them on the list, we thought, ‘Isn’t it too mainstream?’ But you can’t find a full recording today – the recordings are old, they’re not on a digital platform. There was also no editing of the works. All orchestras played with xerox of old material. There was no modern edition of this song.”

From the best known Brazilian composer in the world, Heitor Villa-Lobos, the collection already has some important records. The Choir of the OSESP, conducted by Valentina Peleggi, recorded an album with his transcriptions for choir. The OSESP, conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero, recorded the Concerto for guitar, with Manuel Barrueco, and the Concerto for harmonica, with José Staneck (the same that the OSESP has just presented on its North American tour). In addition, scheduled for May, also with the OSESP, is the launch of cello concerts with Antonio Meneses.

Still, Gustavo de Sá states that, although present, Villa-Lobos was “purposely neglected” in favour of the larger gaps. “The decision has always been up to the artistic direction of the orchestras. There was virtually no conflict.”

Thus, the OSESP also recorded two albums dedicated to Camargo Guarnieri. In the first, Isaac Karabtchevsky commanded the recording of Seresta for piano, with Olga Kopylova, plus Choros for violin (with David Graton), flute (with Cláudia Nascimento) and bassoon (with Alexandre Silvério). The second volume, directed by Roberto Tibiriçá, contains the Choros for clarinet (with Ovanir Buosi), for piano (with Olga Kopylova) for viola (with Horacio Schaefer) and for cello (with Matias de Oliveira Pinto), in addition to the avulsed work Flor de Tremembé.

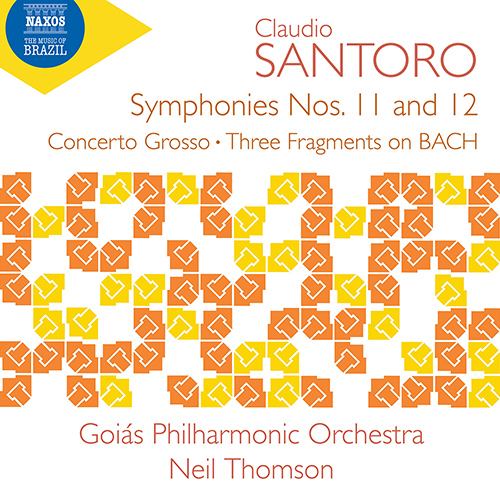

The album that is coming out this month brings the Philharmonic of Goiás under the baton of Neil Thomson, interpreting the Symphonies No. 11 and No. 12 of Claudio Santoro (1919–89), in addition to the Concerto grosso for string quartet and orchestra and the Three fragments on Bach.

“When I came to Brazil to take over the Philharmonic, I wanted to meet the composers of the country,” says Thomson, a British director and principal conductor of the Goiás Philharmonic since 2014. “Friends of mine gave me listening lists. Listening to John Neschling’s and the OSESP recording of Santoro’s Symphonies No. 4 and No. 9, I said to myself: my God, it’s music I can connect with! And I decided I wanted to record his 14 symphonies – an instinctive and impulsive decision, because I hadn’t even heard them all, some were never recorded and others we were even debuting.”

Thomson continues: “I am interested in the beginning of the career of these composers, Santoro and Guerra-Peixe, of the music of when they were students of Koellreutter, not only of the nationalist phase. And Santoro has no limits. His Symphony No. 1, for example, has something from Hindemith, but it already sounds like Santoro. The works of his final phase have electronic elements. He has the widest stylistic range, was always searching. When the album with Symphonies No. 5 and No. 7 came out, some foreign friends said, ‘Well, that’s what we expected, music that has to do with Shostakovich, Carlos Chávez etc.’ And I said to them, wait till you hear Symphony No. 8 or No. 11 – in 17 minutes, he accomplishes everything Shostakovich would take 50 minutes to do. Santoro is never long-winded; he doesn’t waste a note. He has enormous emotional energy. His Symphony No. 11 is very technically demanding – the peak of symphonic writing.”

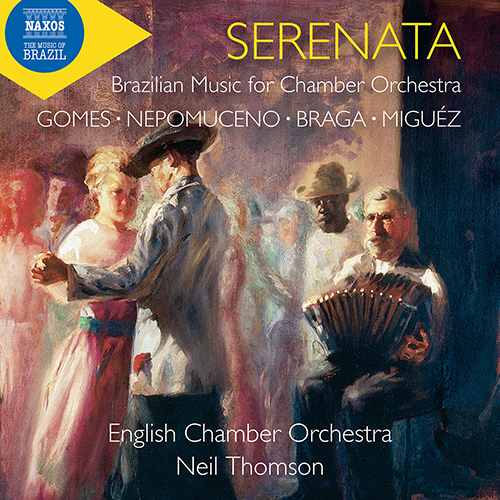

Thomson also directed the album on which the English Chamber Orchestra played works by Miguez, Nepomuceno, Francisco Braga and Carlos Gomes. He says that the Brazilian musical language of the 19th century surprised the English. “When you talk about Brazilian music, you expect something between samba and bossa nova. They were delighted. It’s well written,” he says.

In July next year, comes the album in which Thomson and his orchestra continue the complete orchestral works of Santoro, with Symphony No. 8 and the Cello concerto, with solo by Mariana Martins, followed in September with the title dedicated to Edino Krieger: Fanfares and sequences, Elementary Variations, Ludus Symphonicus, Canticum naturale, Estro harmonic and Three images of Nova Friburgo. And in November, a record in which he conducts the OSESP with creations by Almeida Prado: Symphony of the Orixás and Small Singing Funerals.

With the OSESP, Neil Thomson is also expected to record an album dedicated to Aylton Escobar, who turns 80 in October 2023. In Goiás, after completing the Santoro cycle, the idea is to record the complete symphonies of composer José Siqueira (1907–85), born in Paraíba, northeast of Brazil. “He’s a very interesting composer and even less well-known than Santoro,” he says. Thomson is in favour of immersions in composers’ cycles: “Today, the Goiás Philharmonic feels absolutely at home in Santoro and knows what to do in his music.”

From romantics to the 21st century

Artistic director and titular conductor of the Minas Gerais Philharmonic, Mechetti has explored intensively, but not exclusively, the repertoire of the nineteenth century in the series A Música do Brasil. In addition to the albums already dedicated to Nepomuceno and Carlos Gomes, the orchestra this year will record the symphonies of Henrique Oswald (1852–1931). “I haven’t had access to Symphony No. 2 yet,” says the conductor. “The first is beautiful, romantic, has a certain what of César Franck, of Saint-Saëns. The Brazilian composers of that time were capable of beautiful melodies.”

For the beginning of 2024, it is planned the release of a disc already recorded by the orchestra, with the two symphonies of Oscar Lorenzo Fernandez (1897–1948). “Batuque is a well-known work of Fernandez, but not the symphonies. He was a composer with several resources, knew very well orchestration. And they are not necessarily works of nationalistic language, as you would expect,” Mechetti points out.

In February next year, he will record works by Ronaldo Miranda, who turns 75 in April. “I am very happy with my inclusion in the Naxos series about Brazilian music, with an album dedicated to my symphony production,” Miranda says. “The repertoire will include Time Variations (Beethoven revisited), Horizons and my two works for piano and orchestra: the Concertino for piano and strings and the Piano Concerto for large orchestra. I, Fabio Mechetti and Gustavo de Sá chose Eduardo Monteiro for the piano, great keyboard interpreter. He already has my Concertino in his repertoire and will debut the Concerto in this beautiful phonographic project.”

In January next year, A Música do Brasil is expected to release a record with Santoro’s Fantasias Sul América, played by soloists from the OSESP. Another release that is on the calendar is the composer’s complete solo piano sonatas, in the interpretation of his son, Alessandro Santoro. And there is still to come the album featuring Francisco Mignone (1897–1986) from the OSESP, recorded in August this year, with the Violin Concerto and the Concertinos for clarinet and bassoon, under the conductof Giancarlo Guerrero and with solos by Emmanuele Baldini, Ovanir Buosi and Alexandre Silvério.

According to the accounts of those involved, the project has enough source material to extend for another seven or eight years. Quality repertoire is not lacking.

TO LISTEN

The recordings of the A Música do Brasil collection can be heard on Spotify and other streaming platforms.

CDs can be purchased at the Loja CLÁSSICOS, at www.lojaclassicos.com.br

(Revista CONCERTO, edição 299, Novembro 2022)